Dissolved nutrients

What are the key drivers of the population outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) on the Great Barrier Reef, and what is the evidence for the contribution of nutrients from land runoff to these outbreaks? [Q4.3]

Authors: Ciemon F. Caballes1,2, Katie Sambrook3, Morgan S. Pratchett2

Affiliations: 1Marine Laboratory, University of Guam, 2College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, 3C2O Consulting

Evidence Statement

The synthesis of the evidence for Question 4.3 was based on 183 studies, primarily undertaken within the Great Barrier Reef (but including others for comparison) and published between 1990 and 2023. The synthesis includes a High diversity of study types (38% observational/analytical, 30% experimental, 29% conceptual/review/modelling approaches and 3% mixed) and has a Moderate confidence rating (based on Moderate consistency and Moderate overall relevance of studies).

Summary of findings relevant to policy or management action

Population outbreaks of the coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish represent one of the most significant biological disturbances on coral reefs and remain one of the principal causes of widespread declines in live coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef. Understanding the key drivers of outbreaks on the Great Barrier Reef is fundamental for establishing relevant management responses. There are several hypotheses to explain why outbreaks occur, but they have been typically considered as discrete entities. The most prominent hypotheses include natural causes due to inherent life history characteristics, and others that take into account anthropogenic influences such as the effects of predator removal on different life stages, and water quality changes causing enhanced larval success. This synthesis finds supporting evidence for each of these hypotheses and proposes that the hypotheses are more likely to be complementary rather than mutually exclusive, with a combination of elements resulting in a ‘perfect storm’ that can trigger an outbreak. Combining evidence from the different hypotheses will contribute to a more complete understanding about when, where and how population outbreaks will occur.

Supporting points

- Crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks mostly occur on midshelf reefs in the Great Barrier Reef.

- The body of evidence suggests that primary outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish on the Great Barrier Reef are most likely driven by a combination of the most prominent hypotheses: natural causes, predator removal, and enhanced nutrients.

- Natural causes hypothesis: This hypothesis argues that crown-of-thorns starfish naturally possess inherent life history traits that predispose populations to significant spatial and temporal fluctuations. This hypothesis is supported by evidence of high fecundity, high fertilisation rates, and fast growth that predisposes them to naturally occurring extreme fluctuations in reproductive success and population size. These traits, coupled with the time required for recovery and regrowth of their coral prey, may explain the periodicity (~14 to 17 years) of recurrent outbreaks events on the Great Barrier Reef.

- Predator removal hypothesis: This hypothesis argues that crown-of-thorns starfish populations are normally regulated by high rates of predation on post-settlement life stages and that outbreaks arise when predator populations are reduced (e.g., through fishing). The evidence shows that in areas where fishing is prohibited, the incidence of crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks is generally lower, while the prevalence of sublethal injuries on crown-of-thorns starfish is higher, compared to areas open to fishing. In addition, laboratory, field experiments and modelling studies also indicate that predation rates on post-settlement juveniles can be significant and may regulate crown-of-thorns starfish populations.

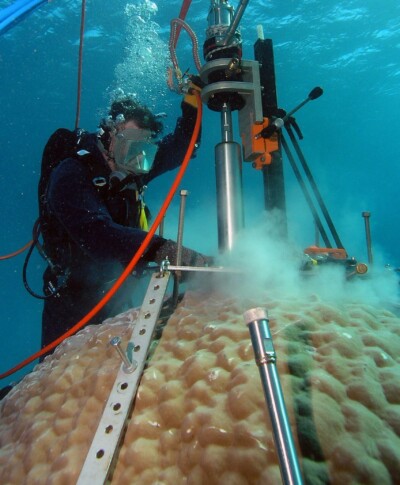

- Nutrient hypothesis: This hypothesis argues that enhanced nutrient supply from river runoff (especially after extreme rainfall events) increases primary production, particularly in coastal and inshore marine waters, resulting in a phytoplankton bloom. Phytoplankton blooms could be beneficial for crown-of-thorns starfish larvae by increasing food supply, thereby promoting faster growth and lower mortality. The following evidential chain was established for this review:

- Nutrient loads delivered to inshore waters and some midshelf sections of the Great Barrier Reef (particularly between Cooktown and Cairns where midshelf reefs are closer to the coast) have increased as a result of historical agricultural development in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area;

- The concentration and availability of nutrients increases following large river discharges, although crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks do not consistently occur in the aftermath of large river discharge events;

- Phytoplankton blooms and shifts in phytoplankton community structure resulting from nutrient enrichment during flood events have been documented, although there is some uncertainty whether phytoplankton concentration (chlorophyll-a levels) or specific phytoplankton species that become dominant during blooms, or a combination of both, is necessary to drive enhanced survivorship and development rates in crown-of-thorns starfish larvae;

- Survival, growth, and development rates are generally higher for well-fed larvae, but there is a lower and upper threshold for optimal food levels;

- The fundamental assumption that larval supply is generally limiting, such that outbreaks arise due to pronounced and temporary increases in larval survivorship due to enhanced food supply, has yet to be explicitly tested; and

- Outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish on the Great Barrier Reef start on midshelf reefs in the Northern sector of the Great Barrier Reef (between Cairns and Lizard Island, and possibly further north), an area commonly referred to as the COTS ‘initiation area’. The ‘initiation area’ overlaps with the area where nutrient-enriched river discharge enter the midshelf waters of the Great Barrier Reef on a regular basis. Larvae produced by primary outbreak populations are subsequently retained on source reefs or dispersed to reefs south of the ‘initiation area’ according to prevailing hydrodynamic regimes, thereby resulting in secondary outbreaks.

- The evidence to date suggests that water quality management programs in isolation will have a limited effect on controlling crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks on the Great Barrier Reef. However, improving water quality through minimising sediment, nutrient, and pollutant runoff, and implementing stricter regulations on fishing, particularly through no-take marine protected areas, offers the best resistance to a natural pest while simultaneously enhancing the resilience of reef ecosystems to withstand or recover from outbreaks.

- In summary, while crown-of-thorns starfish may be naturally predisposed to outbreaks because of key life history traits, it is likely that anthropogenic impacts on water quality and predator fish stocks have exacerbated the incidence or severity of outbreaks, and/or undermined the capacity of reef ecosystems to withstand these cyclic pest irruptions.