Values, condition and drivers of health of the Great Barrier Reef

What is the extent and condition of Great Barrier Reef ecosystems and what are the primary threats to their health? [Q1.2/1.3/2.1]

Authors: Len McKenzie1, Mari-Carmen Pineda2, Alana Grech3, Angus Thompson4

Affiliations: 1Centre for Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research (TropWATER), James Cook University, 2C2O Consulting, 3College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, 4Australian Institute of Marine Science

Evidence Statement

The synthesis of the evidence for Question 1.2/1.3/2.1 was based on 100 studies undertaken within the Great Barrier Reef and published between 2017 and 2022 with this timeframe selected to reflect ‘current’ conditions. The synthesis includes a High diversity of study types (52% observational, 27% modelling, 19% reviews and 2% conceptual), and has a High confidence rating (based on High consistency and High overall relevance of studies).

Summary of findings relevant to policy or management action

Observational studies report that the condition of inshore Great Barrier Reef coral reef and seagrass ecosystems declined marginally from 2017 to 2019 (to Poor condition[1]) due to elevated sea temperatures and heatwaves, tropical cyclones and, additionally in the case of corals, crown-of-thorns starfish. Evidence from 2020 to 2021 has documented recovery of some, but not all, coral reef and inshore seagrass ecosystems. Recovery varied spatially and for coral reefs was less evident or did not occur on inshore reefs from the Burdekin region south or offshore in the Fitzroy region. Mangroves and saltmarsh ecosystems are considered stable and in Good condition[2]. Wetlands are considered stable but in Moderate condition[1] although this varies with wetland types. Based on multiple lines of evidence, the primary threats to Great Barrier Reef marine ecosystems (in order of relative importance) are human-induced climate change, including elevated sea surface temperatures, heatwaves and ocean acidification, and poor water quality from land-based delivery of fine sediments, nutrients, pesticides and other pollutants. For mangroves and saltmarshes, the primary threats are climate change related, including storms, extreme sea level variation and heatwaves. For wetlands, threats include landscape modification and vegetation clearing leading to wetland loss, poor water quality, invasive species, changes in hydrological connectivity, and increasing temperature and salinity from climate change. There is consistent evidence that the resilience of Great Barrier Reef ecosystems is affected by the cumulative impacts of climate change along with local acute stressors such as tropical cyclones and chronic stressors including poor water quality. For marine ecosystems, those nearest to the mainland are at greatest risk from exposure to chronic poor water quality associated with land-based runoff which can have a direct impact but can also impede the ability of these ecosystems to recover from acute pressures.

[1] Reef Water Quality Report Card 2020

[2] Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019

Supporting points

- Great Barrier Reef ecosystems are extensive and diverse; however, not all ecosystems and habitats are equally assessed spatially or temporally, rendering overall condition assessments challenging.

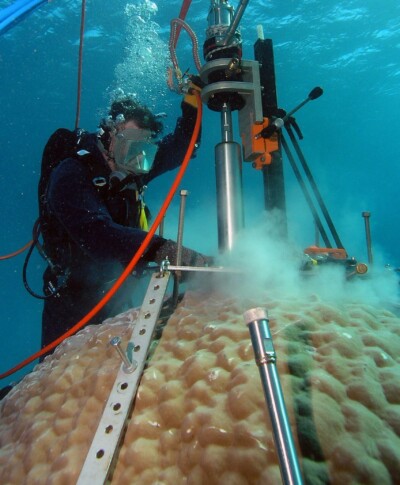

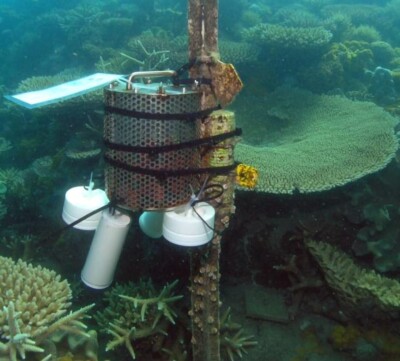

- There are 24,094 km2 of coral reefs mapped within the Great Barrier Reef. The condition of inshore coral reefs from the Wet Tropics to the Fitzroy Natural Resource Management region has declined marginally since 2017 and was categorised as Poor[3] in 2020 to 2021 (based on a multi-indicator resilience index) with regional differences. Hard coral cover on shallow mid- and outer shelf reefs has increased overall since 2017, showing fast recovery from Cooktown to Bundaberg after experiencing losses from repeated mass coral bleaching and/or crown-of-thorns starfish between 2016 and 2019[4].

- The primary threats to Great Barrier Reef coral reef ecosystems are rising sea surface temperature and heatwaves, tropical cyclones, outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish, and ocean acidification. For corals on inshore reefs, their ability to resist or recover from these threats is impeded by additional pressures imposed by land-based runoff and associated impacts such as reduced light, increased macroalgal growth and disease.

- Seagrass meadows are dynamic, changing seasonally in extent and condition, and cover an estimated 35,679 km2. Inshore seagrass meadows across the Great Barrier Reef declined from Moderate abundance and resilience in 2017 to Poor in 2020[3], and while overall condition improved in 2021 (to Moderate), there were continuing declines in the Fitzroy and Burnett Mary regions. These continuing declines were primarily a consequence of above-average discharges from some rivers and disturbance from tropical cyclones.

- The primary threats to seagrass meadows in the Great Barrier Reef are tropical cyclones, land-based runoff (particularly fine sediments and pesticides), and thermal stress from rising sea surface temperatures.

- Other components of the Great Barrier Reef marine ecosystem (pelagic, benthic and planktonic communities) are not included in current monitoring programs and there is limited assessment, however, there are some individual studies that indicate long-term decline in ecosystem condition.

- Although some regional populations of dugongs and turtles are recovering (e.g., southern green turtle), populations of the Great Barrier Reef are in Poor condition and in decline[5]. The greatest threats to dugong and turtle populations are incidental catch (fishing) and loss of habitats (e.g., seagrass loss due to land-based runoff and floods); pollutants in land-based runoff such as trace elements and temperature related feminisation of turtle hatchlings are also important in some locations.

- In Great Barrier Reef estuaries, there are 2,188 km2 of mangroves and 1,757 km2 of salt flats and saltmarshes. Apart from minor localised losses, they are stable and in Good condition[5]. The primary threats to mangroves and saltmarshes are climate change-related including extreme events such as tropical cyclones and storms, extreme sea level variations, and heatwaves.

- In the Great Barrier Reef catchment area, the most recent assessment of wetland extent in 2017 reported 15,556 km2 of mapped wetlands (artificial/highly modified, lacustrine, palustrine, riverine and estuarine), estimated at around 85% of pre-development extent, in stable and Moderate condition[6]. However, the extent varies between wetland types and regions with substantial declines in some areas (e.g., significant losses in extent of palustrine wetlands such as vegetated swamps in the Wet Tropics and Mackay Whitsunday regions of ~49% and ~44% respectively, compared to pre-development estimates).

[3] Reef Water Quality Report Card 2020

[4] AIMS Long Term Monitoring Program

[5] Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019

[6] Reef Water Quality Report Card 2020